MAR 15 2018, 11:41AM

At her debut Deli Gallery solo show, the interdisciplinary artist shares eight of her personal sketchbooks.

The week before Brianna Rose Brooks celebrated her 21st birthday, she opened her first-ever solo exhibition at Deli Gallery in Queens. Love You Coz You Always Tell the Truth collects Brooks’s interdisciplinary artworks, which incorporate drawing, painting, silkscreen printing, and mixed-media practices.

In the middle of the exhibition space, eight of Brooks’s personal sketchbooks sit on a table. Visitors are free to flip through these intimate and dynamic diaries. They span from 2015 — the year Brooks left her native Providence, RI to begin a degree at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago — to the present.

“I still struggle with anxiety, but in high school I was especially socially anxious, and didn’t know how to communicate with people,” Brooks tells me over the phone, after class. “So I drew in sketchbooks and went to the studio. I made things constantly as a way to express those feelings even if I could never find the words to share them with someone else. That’s where my work started, from this place of healing.”

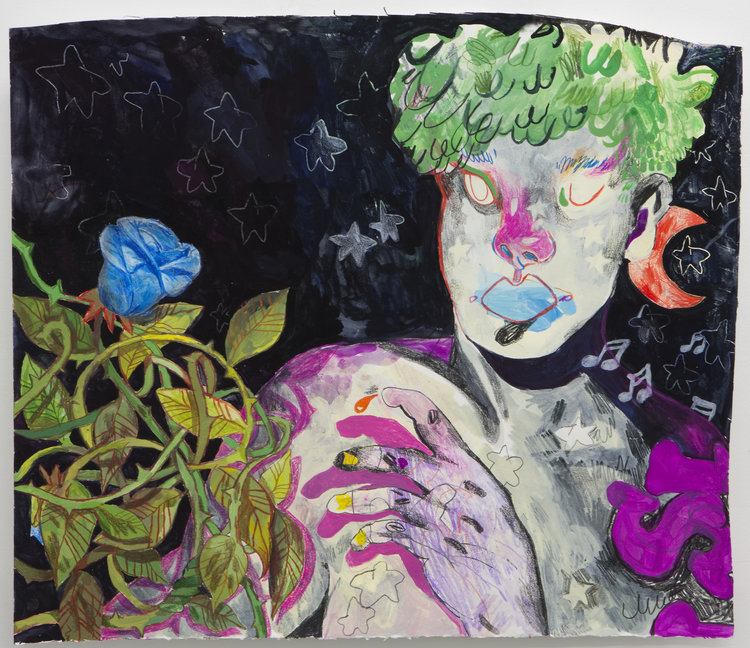

Brooks says she’s most comfortable in her sketchbooks, “where things come naturally, and feel instant.” Perhaps this is why her work feels at once boldly expressive and emotionally introspective. Brooks renders black adolescence through a vibrantly colorful prism of tenderness and love. Her figures dress in zebra prints and chili-pepper-patterns. We find them stretched out on blankets, braiding each other’s hair, puffing on blunts, and in moments of contemplation. They are surrounded by flowers, stars, and rainbows. Sometimes, a halo floats above their gentle green and purple curls.

Below, Brooks shares more about herself and her show.

What was it like growing up in Providence?

Providence is super-small, but there’s a big communal arts scene, especially for inner-city children. I was involved with a program called New Urban Arts for the duration of my high school experience. Local artists teach you everything from screenprinting to sound studio techniques, and you get free access to studio space and supplies. Students are involved in hiring the artists they want to share the space with, so you get really close to your mentors. I spent a lot of time there, and found it was ok to be better at drawing than speaking. I met a lot of different people at different stages of development from all over, and ended up spending a lot of time with RISD students, local DIY artists, zine-makers. Providence is a beautiful, magical little place. I feel most whole there.

What drew you to Chicago?

I didn’t want to apply to RISD and I didn’t get into the school I wanted to. I went to a college prep high school that was very sports and academics-oriented in a way that just didn’t help me. So I struggled a lot. On a last-ditch effort, I applied to SAIC in June, was accepted in July, and moved in August. I’d never been to Chicago before then. So it was a chance, quick decision to move, but it’s been wonderful. Chicago is a beautiful city, and it seems like the type of place people come to work hard. At first, I was overwhelmed, and still find it to be overwhelming at times. The social sphere of art school is not always friendly. But I really value the interdisciplinary nature of it all. You’re never limited by your media. You’re always allowed to bring other things into it, or try new things. And the print scene in Chicago reminds me of the print scene in Providence. It’s friendly and wholesome.

How did your Deli Gallery show come about, and how did you select the work for it?

I’ve been posting my work on Tumblr for years, and Max [Marshall, owner of Deli Gallery] reposted one of my drawings. I was visiting someone in New York over the summer, and was excited about the show that was up at Deli, so we went to see it. The plan initially was to introduce myself, but I wasn’t real enough. When I walked in, I think Max knew who I was, because he’d followed me on Instagram. But both of us were too coy to do anything about it. [Laughs].

I’ve definitely been in that position!

The kinda-smiling-at-one-another across the gallery type of thing. After that, we got to talking, and have been planning the show ever since. In choosing the work: I initially went into it thinking I’d be showing lots of paintings. Large-scale oil paintings that are similar to the one untitled painting that’s in the show. When Max came to Chicago for a studio visit, he looked through my sketchbooks. I posted my sketchbooks online, but I never showed them as serious art pieces, or in a critique space, until this year. People started showing more interest in their intimacy as this honest way of making. It’s sort of voyeuristic to look inside a stranger’s diary, but it feels like an exercise in trust too. Max was attracted to that, and to these other drawings I had started and not finished. All of these things I’d been putting on the backburner as a way to try and “sophisticate” my work by making it more conceptual, doing it in oil, upping the scale. I got to return to this place of making that felt best to me, and was always where I wanted to be, but felt like wasn’t good enough. It was validating to talk about and choose the works from the sketchbooks. I’ve carried many of them with me over the years. They’re like time capsules, but also strange sites of mourning. Ghosts of old relationships and ways of feeling. When they were all set out on the table it almost felt like a final resting place. In displaying them, I’m sort of asking the viewer to share that emotional burden with them, or with me.

Do things typically start for you in a sketchbook?

I feel most comfortable in my sketchbook, and I’m trying to get to a place with larger-scale works that feels similarly spontaneous and intuitive. Which can be challenging. Large-scale works — screen prints, for example — require a lot of prep and thought. Generally, I feel my process has to do with the fluidity of things. It has to flow, and happen naturally. I feel like that’s more genuine. It’s about self-trust more than anything.

Your work is so vibrant and colorful, but many of your figures seem to have reflective, contemplative expressions — suggesting that they might be thinking or daydreaming. Can you say more about that?

Most of the work I make deals with trying to express black identity and love, tenderness, innocence in the same sentiment. So they do come from this place of self-reflection. They have a lot to do with learning, too. I’m trying to express adolescent black identity in a way that’s more kind, and doesn’t write black children off as, essentially, criminals. Black femmes are objectified, demonized, and silenced to the point where we’re hardly seen as fully autonomous, emotional beings. I think these perspectives are rarely present in contemporary art. These ideas we have formed about black bodies and black identities are learned, and I’m interested in propagating a sort of relearning. I’m a very sensitive individual, and when I think about making work, a lot of it has to do with making things I wish I’d been able to see when I was younger — perspectives I wish I had access to when I was a child. So making work is about expressing this narrative that presents an opportunity for other young artists of color to feel like they have a voice within and can be artists and part of the art world.

When I first got to Chicago — which is one of the most racially segregated cities in the country — I was part of 3% of black students at the entire institution. It was really isolating. I want my work to help make others not feel so isolated. Be that emotionally or representationally. When I think about a lot of widely accepted art about black identity, it’s really serious, mournful, and intense. That’s incredibly important, but that’s not all there is to the narrative of blackness. I think experiencing that influenced my pursuit, but communal arts and resources had the most profound impact on my identity. I was surrounded by a huge group of artists diverse in age, race, gender, identity, class, status. I was put on to the reality that as a young person of color, my perspective was valuable and worthy of sharing.